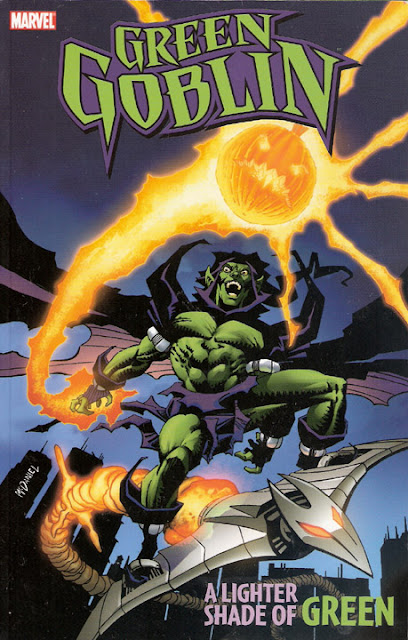

Green Goblin: A Lighter Shade of Green

Collects: Green Goblin #1-13, Web of Spider-Man #125, Spectacular Spider-Man #225, and Amazing Scarlet Spider #2 (1995-6)

Released: August 2011 (Marvel)

Format: pages / color / $39.99 / ISBN: 9780785157571

What is this?: Daily Bugle intern Phil Urich runs across some Green Goblin equipment and tries to decide whether to help himself or others.

The culprits: Writer Tom DeFalco and Terry Kavanagh and artists Scott McDaniel, Joshua Hood, and others

Marvel’s decision to reprint the 1995-6 Green Goblin series in Green Goblin: A Lighter Shade of Green was a curious one. Theoretically, with the Green Goblin being Spider-Man’s archnemesis, a Green Goblin series should have been important. It wasn’t, though; it was a mid-‘90s series about a newspaper intern, Phil Urich, who stumbles across the Osborn Goblin gear. Green Goblin wrapped up just before Onslaught gave Marvel the freedom to do some excellent work with new or lesser-known concepts (Thunderbolts, Deadpool). Neither the writer, Tom DeFalco, nor the main artist, Scott McDaniel, are “hot” or “new” or “critic’s darlings.” As a final nail in the commercial coffin, the character crossed over with the ‘90s Clone Saga.

I suppose Phil becoming the latest Hobgoblin, a recurring villain in Amazing Spider-Man, at the end of 2010 was the impetus for the reprint. Still, that’s a slender thread on which to hang a $40 reprint of a little-remembered, unlamented series like Green Goblin.

Green Goblin is a series that relies heavily its protagonist narrating his thoughts, which is a problem: Phil is a teenager, and when middle-aged white guys write “hip” teenagers, the results always lack verisimilitude. DeFalco seems to have picked up all his teenager dialogue from bad TV shows that were also written by middle-aged white guys. Although Phil does have a distinctive voice, I don’t believe anyone has ever spoken like him in the history of mankind — unless, by chance, some grunting caveman or cavewoman accidentally strung together the same syllables Phil used. I was a teenager in the ‘90s, and I can guarantee none of my friends ever used phrases like “Scarlet really ups the gear” or “she’s mint, sexy, and all that!” I didn’t either — or at least I don’t remember sounding like that. Might explain my social life if I did say those sorts of things. Slammin’!

Green Goblin is a series that relies heavily its protagonist narrating his thoughts, which is a problem: Phil is a teenager, and when middle-aged white guys write “hip” teenagers, the results always lack verisimilitude. DeFalco seems to have picked up all his teenager dialogue from bad TV shows that were also written by middle-aged white guys. Although Phil does have a distinctive voice, I don’t believe anyone has ever spoken like him in the history of mankind — unless, by chance, some grunting caveman or cavewoman accidentally strung together the same syllables Phil used. I was a teenager in the ‘90s, and I can guarantee none of my friends ever used phrases like “Scarlet really ups the gear” or “she’s mint, sexy, and all that!” I didn’t either — or at least I don’t remember sounding like that. Might explain my social life if I did say those sorts of things. Slammin’!A second problem with Phil’s narration is that Phil is not an intrinsically likeable person. Phil is one of those slackers DeFalco had heard so much about, a college dropout working as an intern for his uncle, Ben Urich, at the Daily Bugle. Having dropped out of college, Phil doesn’t know what he’s going to do with his life, and when he gets the Green Goblin equipment, he’s not sure how he wants to use it. He doesn’t instinctually aid others, but he usually ends up being helpful. He has vague ideas of gaining fame, acclaim, money, and women, but his plots are badly thought out, and they lack ambition. Also, Phil’s a bit skeevy about the women; he notes when Lynn, the girl he has a crush on, “jiggles into view” and thinks about “all the butter [he] wanted to spread on Lynn.” It’s no surprise that when he gets some money, he spends it on a suit and flowers and expects Lynn to fall into his arms, despite his lack of charm and her general lack of interest in him as anything but a co-worker and source of info.92

DeFalco does a good job choosing sparring partners for Phil to fight, mixing established villains with new ones. Hobgoblin is a no-brainer, considering he was, at the time, the only other living link to the Goblin legacy. Arcade is always a good choice for a beginning hero. Yes, it stretches credibility that Phil would be able to defeat the Rhino early in his career, but in issue #2, the hero needs a victory, and in a battle between two lunkheads, I can buy that the first person with a good idea would win. The new villains are a mixed bag; Angel Face is the most competent and has a real reason to keep after the Green Goblin, and the Steel Slammer has a nice design. Purge, a generic assassin, and Jonathan Gatesworth, a “virtual reality” creator, are forgettable.93

Even beyond DeFalco’s failed attempts to emulate the youth slang of the day, Green Goblin is marked pretty solidly as a ‘90s comic by DeFalco working current events of the comic-book industry into the background. At one point, recurring villain Angel Face robs a tycoon named “Berinutter,” which sounds like DeFalco’s way tweaking the nose of or taking his frustrations out on Isaac Perlmutter, who was chairman at the board at Marvel at the time. DeFalco also makes “Larson Toddsmith” and “Marc Portaccio” the unscrupulous heads of Compuboot, a game company; the names are obvious references to Image Comics founders Erik Larsen, Todd McFarlane, Marc Silvestri, and Whilce Portacio.

Marvel’s financial situation was worsening at the time, and DeFalco has some opinions on how business and creative pursuits should intersect; in #9, he puts these words into a villain’s mouth: “[We] would be in Chapter 11 if not for [our] financial wizardry and … marketing magic! Creativity is fine … in its place … but the business people transform vague ideas into profits!” Later in the issue, he puts the opposite view into Phil’s mousy potential love interest, Meredith Campbell: “Corporations don’t think like us regular folks! No matter how much profit they generate … it’s never enough!” The joke was on DeFalco, though, as Marvel filed for Chapter 11 in December 1996, a few months after Green Goblin was cancelled.

The book includes three Spider-issues. The best is a crossover between Amazing Scarlet Spider #2 and Green Goblin #3, which is part of the Great Game storyline. Phil gets a crush on the amoral Joystick, who fights in the Great Game, an international gladiatorial contest. Joystick is in town to fight the Scarlet Spider, but her plans are loused up by one of her previous victims, El Toro Negro. DeFalco had an excellent chance to contrast the attitudes of the thrill-seeking Joystick and responsible Scarlet Spider, especially since the Scarlet Spider doesn’t have Spider-Man’s cachet as a moral center of the superhuman community. Instead, DeFalco treads too lightly on the question, having Phil reject Spider-Man’s ethos without seeing his own similarities to Joystick.

Web of Spider-Man #125 and Spectacular Spider-Man #225, which immediately follow Green Goblin #1 in this volume, seem like the traditional attempts to boost a new character’s profile with an appearance in a Spider-book. Unfortunately, the two issues serve as poor attempts at promotion, since the Green Goblin in those books little resembled the one who starred in his own book. Web #125, written by Terry Kavanagh, is the worst offender, as Phil’s motivations for being in the Clone-Saga story are weak at best and nonsensical at worst. Spectacular #225 is written by DeFalco, but Phil’s reasons for being out in costume are not in line with his development in his own series; Phil sees himself on a “grim mission” when he hunts down a man setting fire to homeless people, which is quite heroic for someone who hasn’t decided what to do with his new powers. His inexperience does show in his battles with the villain and Spider-Man, though.

DeFalco keeps bringing up Phil’s struggles with his identity: is he a hero or someone who merely exploits his abilities for personal gain? An ambitious man or slacker? Ladies man or creep? Although Phil arrives at the place you expect him to by the series’ end, it is sometimes hard to follow his developmental path. He eventually overcomes his fear of the neighborhood thug, Ricko the Sicko, but he still fears the Hobgoblin’s wrath. He rejects Lynn not because he finds a woman whom he is more compatible with but because he realizes Lynn isn’t that interested in him. His heroism is motivated as much by a desire to impress Lynn as his nascent conscience, despite advice from Daredevil and Scarlet Spider. Only the Onslaught crisis forces him to answer the questions, and then the series ends.

The primary artist for Green Goblin, Scott McDaniel, has a blocky, exaggerated style that works best in the ‘90s. The Green Goblin costume and mask lends itself to exaggerated touches, and I like the Steel Slammer design, but he has a little trouble with Phil’s quieter moments. (McDaniel’s Pittsburgh youth shows up when he has Phil wear a Steelers jacket, even though Phil’s a fan of the New York Smashers.) McDaniel penciled #1-4, 6-7, and 9-10, leaving a lot of space for fill-in artists. Most of these are unremarkable, with the occasional glitch; for example, Keven Kobasic draws Judge Tomb as a tall, powerful young man with single tufts of blond hair on his head and chin in #5, while McDaniel goes the more clichéd route, depicting Tomb as a small, old man with a fringe of white hair on his head in #6.

Joshua Hood drew the last three issues. Hood’s distorted, elongated faces are off-putting, making the characters look almost deformed. He draws Angel Face’s scars as far more disgusting than McDaniel did, robbing her of some of her humanity (which DeFalco’s writing doesn’t compensate for). In #12, though, his Sentinels aren’t bad, and the final image from that issue is impressive.

Joshua Hood drew the last three issues. Hood’s distorted, elongated faces are off-putting, making the characters look almost deformed. He draws Angel Face’s scars as far more disgusting than McDaniel did, robbing her of some of her humanity (which DeFalco’s writing doesn’t compensate for). In #12, though, his Sentinels aren’t bad, and the final image from that issue is impressive. Green Goblin grades out as mediocre — not groundbreaking or very memorable, but it’s not offensive either. Poking around these forgotten corners of the Marvel Universe is always its own reward, but on the other hand, it’s not a reward worth paying $40 for (or $30 new at Amazon). If you are an archaeologist of Marvel or ‘90s pop culture, Green Goblin might be worth it if you can find it at a reasonable price. Otherwise, let it go.

Rating:

Labels: 2, 2011 August, Green Goblin, Joshua Hood, Marvel, Phil Urich, Scott McDaniel, Steel Slammer, Tom DeFalco