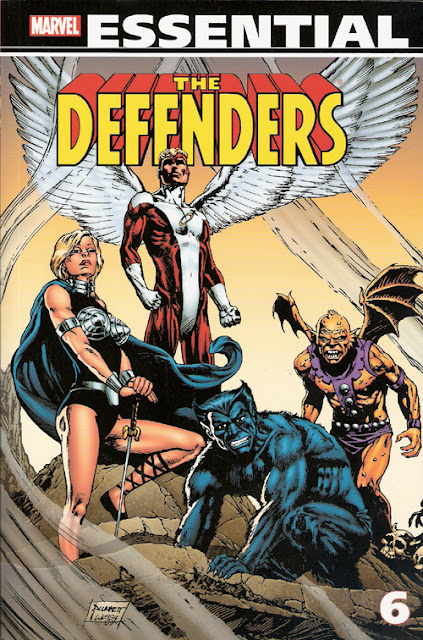

Essential Defenders, v. 6

Collects: Defenders #107-25, Marvel Team-Up #119, and Avengers Annual #11 (1982-3)

Released: September 2011 (Marvel)

Format: 528 pages / black and white / $19.99 / ISBN: 9780785157540

What is this?: The Defenders spiral toward the non-team’s dissolution.

The culprits: Writers J.M. DeMatteis and artist Don Perlin

A couple of weeks ago I reviewed Batman: The Court of Owls, a recent title that might be of interest to a general audience. Last week, it was Chronicles of Conan, v. 21: Blood of the Titan and Other Stories, which — since it reprints stories almost 30 years old — has a more limited appeal. This week I remain in the past, turning my back on relevance with Essential Defenders, v. 6, another set of early ‘80s stories from late in the title’s run.

Not that I think there’s anything wrong with looking at a random slice of issues from near the end of Defenders. Every title has troughs and crests in quality; Defenders certainly had high points well after issue #1 in ‘72. I liked parts of Essential Defenders, v. 5, even if the previous volume was a bit weak. There’s no reason why some of the greatest Defenders issues couldn’t have been released in the early ‘80s, between #107-25.

But are there great issues in there? No, not really. Could’ve been, though.

But are there great issues in there? No, not really. Could’ve been, though.J.M. DeMatteis wrote all but one issue in this collection (Steven Grant wrote #119, a flashback issue that has all the hallmarks of an inventory story that had to be used before the title’s status quo changed). DeMatteis is best known — to me, at least — for writing psychological Spider-Man stories, like Kraven’s Last Hunt and The Child Within (Spectacular Spider-Man #178-84). Basically, if you wanted a story where a Spider-Man villain cries about a difficult / tragic childhood, DeMatteis was your man.

In v. 6 DeMatteis concentrates on the theme of identity, potentially an interesting idea on a non-team in which few members can define themselves in terms of the team. Valkyrie seems to die, but she returns in a new / old Asgardian body — her original, not the one she co-opted because of the Enchantress’s spell that brought her to Midgard in the first place. She looks the same — of course; it’s magic — but everyone talks about how different she seems emotionally. DeMatteis devotes a story to Devil Slayer’s issues — Devil Slayer, everyone’s favorite Marine / alcoholic / hitman / cultist / supernatural killer with a teleportation cloak. The story involves hallucinations and drinking and many, many manly tears. Hellcat goes on a journey to discover if she’s really the daughter of the devil; Nighthawk deals with mind control and implanted memories; Hellstrom finds a double has taken the life he abandoned at District University in Washington.

Some of these are interesting in concept, such as Valkyrie’s transformation or the glimpse of the supporting cast Hellstrom abandoned in Son of Satan (reprinted in Essential Marvel Horror, v. 1). But few are interesting in execution, with the low point being in #116, in which new character Overmind seems to be trying to make the lonely Dr. Strange more miserable by showing him couples in love (or struggling with love).

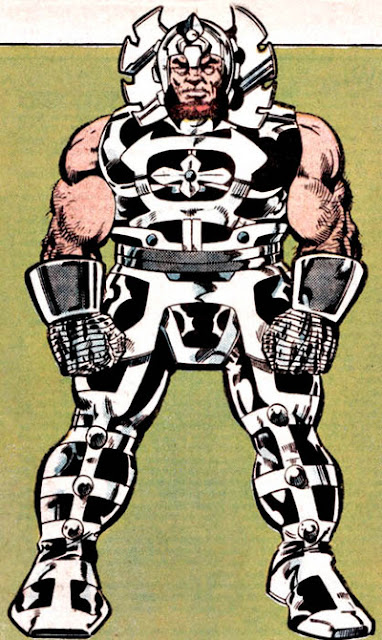

The Overmind is symptomatic of the book’s biggest problem. It isn’t that the telepathic lug is little more than a vivid visual and a power set; many characters start that way and still go on to long lives. But he’s a big part of the book straying from its roots. The Defenders are a non-team, which causes a fluid membership. Characters come and go, yes, but most of the solid core remains: Dr. Strange, Hulk, Hellcat, Nighthawk, and Valkyrie. DeMatteis forcefully pushes most of those characters aside by the end of v. 6, but you can see them slowly being edged out before that. Beast, former X-Man and Avenger, is the instigator, pushing for more conformity and becoming “leader” of the team by #125. He makes the defenders into the de facto first X-Men spinoff by adding Angel and Iceman to the roster. By the end, only Beast and Gargoyle remain from #107; Valkyrie is with the team as well, but as mentioned above, it’s ostensibly a different Valkyrie.

The Overmind is symptomatic of the book’s biggest problem. It isn’t that the telepathic lug is little more than a vivid visual and a power set; many characters start that way and still go on to long lives. But he’s a big part of the book straying from its roots. The Defenders are a non-team, which causes a fluid membership. Characters come and go, yes, but most of the solid core remains: Dr. Strange, Hulk, Hellcat, Nighthawk, and Valkyrie. DeMatteis forcefully pushes most of those characters aside by the end of v. 6, but you can see them slowly being edged out before that. Beast, former X-Man and Avenger, is the instigator, pushing for more conformity and becoming “leader” of the team by #125. He makes the defenders into the de facto first X-Men spinoff by adding Angel and Iceman to the roster. By the end, only Beast and Gargoyle remain from #107; Valkyrie is with the team as well, but as mentioned above, it’s ostensibly a different Valkyrie.To effect this changeover, DeMatteis wastes considerable pages over the final four issues on a vague prophecy that shuffles the Big 4 Defenders (Strange, Hulk, Namor, and Silver Surfer) off stage. To do this, he gives resolution to previous writer Steve Gerber‘s “Elf with a Gun” story. There was never any sense behind the “subplot” — Gerber wrote one-page vignettes of an Elf shooting people, apparently without any purpose behind it — but DeMatteis retroactively gives those bits of silliness meaning. It does not improve the previous installments, and tying the Elf to an attempt to write out long-term Defenders does no favors to DeMatteis’s story either.

Robbing that story of its whimsy is somewhat fitting for this volume; most of the strange, silly fun of the Defenders is missing inv. 6, replaced by DeMatteis’s heavy introspection. I don’t know whether the new direction DeMatteis wrenched the book toward was his or editorial’s, but it ill suits the book. It’s all a bit too obvious, too heavy handed for a freewheeling, fluid book like the Defenders.

Looking of the review so far, it sounds like this book is a completely failure, or nearly so. But there are some enjoyable moments. As I mentioned, Hellstrom finding someone has picked up his discarded life at District University is a neat idea and symbolically suggests the nature of a shared universe. Grant’s fill-in reminds readers of vintage Defenders — it’s set between #68 and 69, actually — and even if it is a bit tried and true, it does have Sal Buscema pencils, so I can forgive the story for not being the most innovative. DeMatteis obviously enjoys writing the Beast, and even if this isn’t my favorite interpretation of the character, he is still frequently amusing. The funniest issue is #115, in which Beast, Valkyrie, Gargoyle, and Namor are thrown into a faux-Seuss dimension; I wish Namor could have vented his frustration on the overly sweet homages, but sadly, it was a Code-approved comic.

Still, that’s not enough to let me recommend v. 6 — nowhere close, really. If you really like Beast or think previous volumes of the Essential Defenders were a touch too silly or weird, then this might be for you. Otherwise …

Or maybe if you’re a Don Perlin fan — I haven’t met any of those, but I think they’re probably out there. Perlin, who drew most of the issues in v. 6, is … fine: competent, dependable, not prone to drown in any stylistic excuses. His name probably sold few books in his time, but he was a Marvel mainstay for a reason, and you can see that reason throughout v. 6.

Given that #125 ifs the first issue of the New Defenders, you might think this (or the next volume) is a good jumping on point. Not so fast, Alphonse; you have to look at what you leap into. The New Defenders are not that fondly remembered — a 27-issue run that ended when Iceman, Beast, and Angel were needed for the launch of X-Factor, and the rest of the team was unceremoniously jettisoned into the Great Beyond. You could jump on there. Would you want to? And if you wanted to, why not do it in color with the New Defenders trade paperback, which reprints #122-31? Even I, completist that I am, have decided to end my Defenders collection with this volume. I don’t think it’s much of a decision, though, as there is little chance the New Defenders will get an Essential of its own.

Essential Defenders, v. 6, has little to recommend it beyond its value to completists. Pass on it unless you’re really into the non-team.

Rating:

Labels: 1.5, 2011 September, Beast, daimon hellstrom, Defenders, Devil Slayer, Don Perlin, Elf with a gun, Hellcat, J.M. DeMatteis, Marvel, Overmind, Valkyrie

(2.5 of 5)

(2.5 of 5)