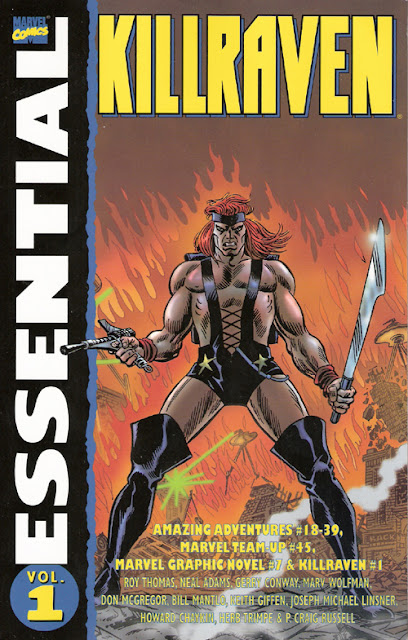

Essential Killraven, v. 1

Collects: Amazing Adventures #18-39, Marvel Team-Up #45, Marvel Graphic Novel #7, and Killraven #1 (1973-6, 1983, 2001)

Released: July 2005 (Marvel)

Format: 504 pages / black and white / $16.99 / ISBN: 9780785117773

What is this?: A former gladiator and his companions fight against the Martians who have enslaved Earth.

The culprits: Writer Don McGregor and others and artists P. Craig Russell, Herb Trimpe, and others

The setup for Killraven is one of those sci-fi concepts Marvel came up with in the ‘70s that didn’t survive beyond the Bronze Age. Created by writer Roy Thomas and artist Neal Adams, it has a simple hook: the Martians, after losing the original War of the Worlds, won the rematch in 2001 and subjugated humanity, and only an ex-gladiator named Killraven and his band of Freemen oppose them.

If you’ve ever seen Thundarr the Barbarian — and if you haven’t, I pity you — Essential Killraven, v. 1, might be a little familiar. Killraven fights the Martians (wizards for Thundarr) and lots of monsters. He visits American cities that, despite being ruins, have one distinguishing feature from the pre-war days. Humans have been shaped into weird forms and given superpowers. And then there are the aliens who eat babies …

Wait. That last one wasn’t on TV. And that’s where writer Don McGregor, who took over with Amazing Adventures #21, makes Killraven something other than a needless continuation of a sci-fi classic. His stories have babies eaten as delicacies, forced breeding, and humans tortured, warped, and killed for no real reason. Yes, the casualty rate for Killraven’s band of Freemen is absurdly low, but even they are touched by loss, and why are you complaining? This was a comic book meant for kids, and they’re talking about eating babies because they’re yummy.

Wait. That last one wasn’t on TV. And that’s where writer Don McGregor, who took over with Amazing Adventures #21, makes Killraven something other than a needless continuation of a sci-fi classic. His stories have babies eaten as delicacies, forced breeding, and humans tortured, warped, and killed for no real reason. Yes, the casualty rate for Killraven’s band of Freemen is absurdly low, but even they are touched by loss, and why are you complaining? This was a comic book meant for kids, and they’re talking about eating babies because they’re yummy.

The major flaw in Killraven is that the setup lends itself to a lot of repetition. The Freemen head to a new town, fight the weird menace, and then find themselves in a new place at the beginning of the next issue. McGregor does his best to play with that, especially at the end, when he has Freeman Old Skull tell the others his origin story (#37) or has the group run into a fairy-like creature named Mourning Prey in a butterfly-filled Florida swamp (#39), an issue that has the slight tinge of a fever dream about it. But he can’t disguise that repetition, and his comic-booky “man who lives for only one day and must mate” plot (#35) certainly gives that issue the feel of just another Marvel book, despite its trappings. (Bill Mantlo’s fill-in on #33 and his Marvel Team-Up Killraven story only compound the feeling.) Still, McGregor is good for some surprises; when Carmilla Frost joins the Freemen, for instance, it’s Killraven’s friend M’Shulla, not Killraven, who gets the girl.

Additionally, there’s something completely endearing about a comic in which the hero gets so lost that while heading to Yellowstone National Park to find his brother that he travels instead from Indianapolis to Michigan to Chicago to Tennessee to Georgia to Florida. Killraven has no sense of direction, and it appears his cohorts have no desire (or ability) to correct him. To be fair to Killraven, he can’t exactly ask the mutants, collaborators, monsters, and Martians directions on the way, and everyone else they meet is even more clueless than they are. Even more entertaining is that Yellowstone is obviously a trap, and the Martians get so impatient they move the trap to where Killraven is wandering (Cape Canaveral) and don’t bother to disguise it at all. The amusing cherry on top of it all is that Killraven doesn’t question meeting his brother thousands of miles from where each is supposed to be at all. “My brother’s supposed to be in Yellowstone and just runs into me in Florida? Sure, why not?”

That happens in Marvel Graphic Novel #7, and without that issue, this wouldn’t be half as good a book. Without the MGN, Killraven is a meandering story in which McGregor takes his heroes across the eastern U.S. Sure, that gets better as the book goes on, but the story just sort of peters out in Amazing Adventures #39 when the Freemen encounter Mourning Prey. But MGN #7 puts paid to the big motivation for the Freemen’s journey: finding Killraven’s brother. It doesn’t go very well for the characters, but it does end the plot, something that needed to be done.

The obvious way to end the series in MGN #7 would have been with Killraven and the Freemen fighting back against the Martians, leading a revolution. Unfortunately, while that might be a definitive ending, that sort of ending is rarely satisfying: not enough buildup, too many characters, too improbable a plot, or a hundred other problems. Instead, McGregor and artist P. Craig Russell give the readers one reveal, but they do so in a plot much like previous stories. Oh, their ally for the story is more developed and relatable than most of those in the Amazing Adventures run, but it tonally fits with the rest of the story. McGregor even develops Carmilla and M’Shulla’s relationship, as if he expected to write more stories Killraven. (According to McGregor in this interview with Richard Arndt, 50 or so pages of Killraven: Final Lies, Final Truths, Final Battles was written in the late ‘80s, but it was scuttled when Russell couldn’t get assurances it would be published in Marvel’s best format.)

And the art …

Much like Bill Sienkiewicz and Moon Knight, Russell’s art is the biggest selling point for Killraven, and the MGN is where Russell gets the opportunity to show off the most. It’s unfortunate that the size of the art had to be reduced for the Essential’s page dimensions, and for some reason the art isn’t reproduced in the pure black-and-white pencils and inks the rest of the book features. But even the slight muddying can’t hide Russell’s skill or maturation; he was excellent in issues #27-32 and 34-9, but in the years between Amazing Adventures and MGN #7, he’s become something else. The art is polished, fluid, and expressive. His figures all have a litheness about them — even some who shouldn’t, like Old Skull — but his monsters are bizarre, horrific, and most important alien.

Russell wasn’t the first artist on the title. Adams did the first half of the first issue and was followed by one and a half issue by Howard Chaykin; both do good, if brief, work, but we have Adams to blame for the horrible, horrible costume designs. (What the hell did they think the future would be like back then? This is one Essential I was glad had no color, fearing that a ‘70s palette on those ridiculous costumes would sear my eyes.) Although a mismatch of genres, Gene Colan did his usual atmospheric work on one issue (#26). Herb Trimpe (#20-4 and 33) and Rich Buckler (#25) round out the art duties, both doing solid work. Trimpe’s work is similar to the art he produced for the Hulk; Buckler’s work is interesting, more subtle and clear than the other artists.

The book concludes with the Killraven one-shot written and drawn by Joe Lindsor. To call it missable is an understatement of grand proportions; if I had paid for the single issue when it came out in 2001, I would have wanted my money back. There’s nothing in the issue for Killraven fans, except that it advances the timeline without incident by a half year or so. The actual plot, in which Killraven counsels a hippy chick who woke from a cryogenic tube and then promptly wants to go back to sleep when she sees what a hellhole 2020 is, is so light I was afraid it might blow off the page. It was included to fill out the page count, I imagine, but 20 blank pages might have been a better choice.

Essential Killraven is often silly (it is a product of the ‘70s), frequently repetitive, and occasionally stupid (as when McGregor tries to convince us “mud brother” is a term of endearment that Killraven has given M’Shulla instead of the racial slur it so obviously seems to be). But Killraven is worth a glance for some of the details and the P. Craig Russell art.

Rating: ![]()

![]()

![]() (3 of 5)

(3 of 5)

Labels: 2005 July, 3, Atlanta, Battle Creek MI, Chattanooga, Chicago, Don McGregor, Essentials, Florida, Herb Trimpe, Indianapolis, Killraven, Marvel, Nashville, P. Craig Russell, West Virginia

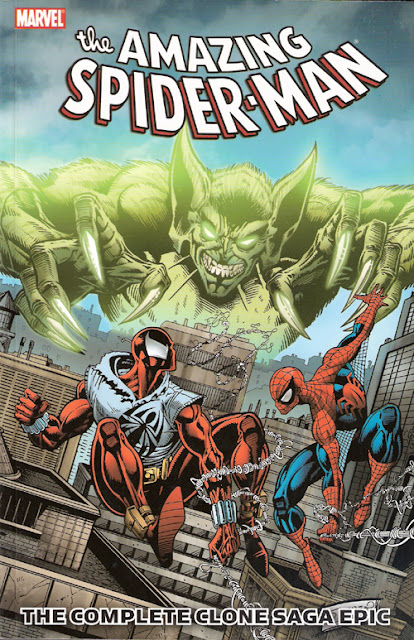

Yes, I said “fun.” It’s not a classic, and if you were looking for a Spider-Man story, there are a couple dozen others I would recommend first. But I can’t deny I found the book interesting and sometimes exciting, despite the plot being spoiled long ago.

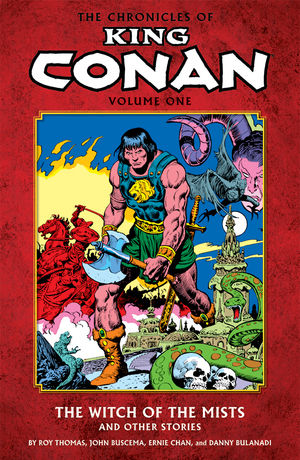

Yes, I said “fun.” It’s not a classic, and if you were looking for a Spider-Man story, there are a couple dozen others I would recommend first. But I can’t deny I found the book interesting and sometimes exciting, despite the plot being spoiled long ago.  You would be wrong. Conan the King is the exact same character as Conan the Barbarian. True, Conan has an army behind him, and he has a son, but it has remarkably little effect on his behavior. And Thomas should know; forty years after Conan the Barbarian #1, v. 1, and Thomas is still the definitive Conan comic book writer.

You would be wrong. Conan the King is the exact same character as Conan the Barbarian. True, Conan has an army behind him, and he has a son, but it has remarkably little effect on his behavior. And Thomas should know; forty years after Conan the Barbarian #1, v. 1, and Thomas is still the definitive Conan comic book writer.